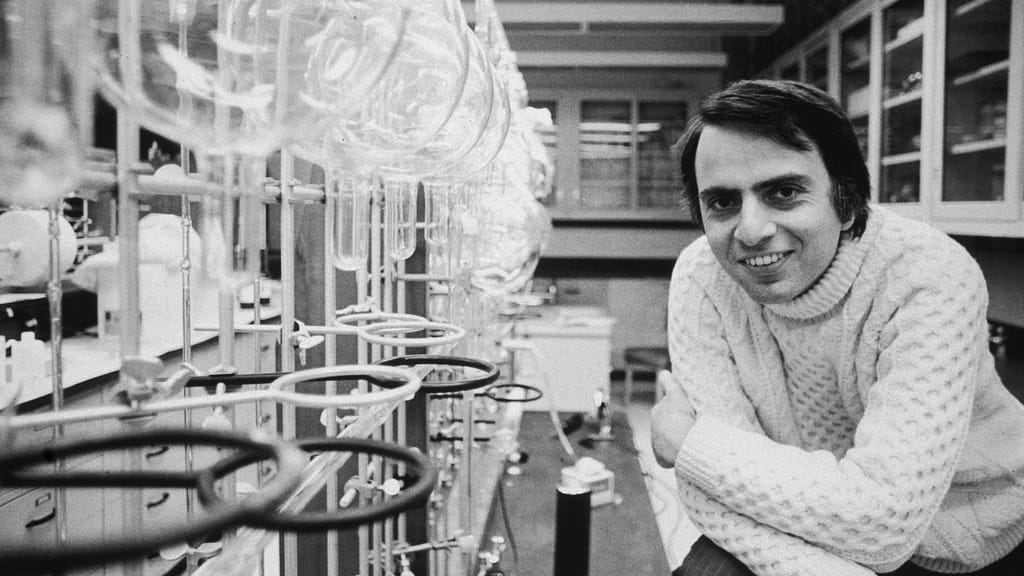

On what would’ve been the astronomer’s 90th trip around the sun, here’s a look at his legacy as a scientist, advocate and communicator.

Though regrettably without Sagan, who passed away in 1996 at the age of 62, the globe will commemorate Carl Sagan’s 90th birthday on November 9, 2024.

His co-creation and hosting of the 1980 “Cosmos” television series, which hundreds of millions of people watched globally, is what most people remember him for. Others read “The Dragons of Eden,” his Pulitzer Prize-winning nonfiction work, or “Contact,” his best-selling science fiction. He promoted astronomy to millions more on “The Tonight Show.”

The vast influence of Sagan’s research, which is still relevant today, is something that most people are unaware of and that his notoriety has partially masked. Sagan was a prolific writer, a brilliant advocate, and an unparalleled science communicator. However, he was also a superb scientist.

Sagan made at least three significant contributions to the advancement of science. His noteworthy findings and discoveries have been documented in more than 600 scholarly publications. He made it possible for new scientific fields to thrive. He also served as an inspiration to several generations of scientists. Such a combination of skills and achievements, in my opinion as a planetary scientist, is uncommon and might only happen once in my lifetime.

Scientific accomplishments

In the 1960s, very little was known about Venus. Sagan looked into how Venus’s excessively high temperature of about 870 degrees Fahrenheit (465 degrees Celsius) may be explained by the greenhouse effect in its carbon dioxide atmosphere. His study continues to serve as a warning about the perils of pollution from fossil fuels on our planet.

Sagan offered a convincing explanation for Mars’ seasonal variations in brightness, which had previously been mistakenly ascribed to volcanic activity or vegetation. He stated that the enigmatic differences were caused by dust carried by the wind.

Sagan and his students investigated how our climate is impacted by variations in the reflectance of the Earth’s atmosphere and surface. They thought about how nuclear bomb explosions may release so much soot into the atmosphere that it would cause a significant cooling spell for years, a phenomenon called “nuclear winter.”

Sagan advanced the emerging field of astrobiology, or the study of life in the cosmos, with his exceptional depth of knowledge in astronomy, physics, chemistry, and biology.

In groundbreaking laboratory experiments, Sagan and Cornell University research scientist Bishun Khare demonstrated that specific prebiotic chemistry ingredients, known as tholins, and specific life-building components, known as amino acids, naturally form in lab environments that replicate planetary conditions.

He was also heavily involved in the biological studies on the Mars Viking landers, and he analyzed how asteroids and comets might bring prebiotic compounds to the early Earth. Sagan also conjectured that creatures like balloons may float in the atmospheres of Jupiter and Venus.

His desire to discover extraterrestrial life was not limited to the solar system. He was an advocate of SETI, or the hunt for alien intelligence. He partnered with electrical engineer and physicist Paul Horowitz to scan 70% of the sky as part of a systematic hunt for extraterrestrial radio beacons, which he helped fund.

He suggested and co-designed the plaques and “Golden Records” that are currently attached to the Pioneer and Voyager spacecraft, humanity’s furthest-flung ambassadors. Although it is doubtful that these artifacts would ever be discovered by aliens, Sagan wanted people to think about the potential for contact with other civilizations.

Advocacy

Sagan’s contributions to science have consistently made him a persuasive speaker on matters of scientific and societal importance. He discussed the risks posed by climate change in his testimony to Congress. He was a vocal opponent of nuclear power and the Strategic Defense Initiative, popularly referred to as “Star Wars.” In an effort to strengthen ties between the US and the USSR, he called for cooperation and a joint space expedition. He created a petition signed by hundreds of well-known scientists seeking support for the hunt for alien intelligence and had direct conversations with members of Congress about it.

However, his encouragement of critical thinking and truth-seeking may have been his greatest contribution to civilization. He urged individuals to have the self-control and humility to challenge their most held ideas and to rely on facts in order to have a more realistic perspective on the world. “The Demon-Haunted World: Science as a Candle in the Dark,” his most often quoted work, is an invaluable tool for anybody attempting to make sense of this disinformation-filled era.

Impact

The frequency with which other scientists mention a scientist’s academic work can occasionally be used to measure that scientist’s influence. Sagan’s work continues to receive over 1,000 citations annually, according to his Google Scholar profile.

According to the National Academy of Sciences’ website, members are “elected by their peers for outstanding contributions to research,” which is “one of the highest honors a scientist can receive.” His current citation rate is in fact higher than that of many of these members.

At the annual conference, Sagan’s nomination to be elected into the academy during the 1991–1992 cycle was contested; almost one-third of the members voted against him, ensuring his expulsion. “Jealousy is the worst of human frailties that keeps you out,” a meeting observer wrote to Sagan. Others in present confirmed this opinion. The academy’s refusal to accept Sagan, in my opinion, is still a permanent disgrace to the institution.

Sagan left behind a rich and extensive legacy that cannot be diminished by jealousy. Sagan has inspired generations of scientists and instilled a love of science in countless nonscientists, in addition to his scientific achievements. In the fields of lobbying, communication, and science, he has shown what is feasible. Truth-seeking, diligence, and self-improvement were necessary for their achievements. A fresh dedication to these principles would pay tribute to Sagan on the 90th anniversary of his birth.